Recensie (840)

Sorry We Missed You (2019)

Another of Ken Loach’s angry social dramas, Sorry We Missed You reveals level by level why precarity of work is one of the worst symptoms of the current economic model. The uncompromising and deliberately frustrating conclusion evokes compassion and anger, the combination of which both arouses interest in those who are paying the highest price for maintaining neoliberalism and provokes action. Therefore, this is an important film and, together with the Irish drama Rosie, one of the best films that have been made on the topic of workers’ lives in recent years. 80%

Diane (2018)

In his belated feature-film directorial debut, former film critic and documentary filmmaker Kent Jones offers a sensitive character study of a working woman from a small city who forgets to take care of herself as you she takes care of others. With every scene, this long-resonating, stylistically unobtrusive film is remarkably rich in meaning. Diane relies on a highly subjective narrative, the director’s sense of detail and the deeply felt acting of Mary Kay Place, which strengthens our affinity for the main protagonist while contributing to doubtfulness with respect to her mental health. The film is also valuable due to the matter-of-factness with which it states that at the end of our life story, no major point will be revealed, but only death in loneliness. 80%

Anthropocene: The Human Epoch (2018)

Stunning shots that are more truthful than those with which series like Planet Earth captivate us (though we could discuss the paradox that lies in the attempt to show devastation in a manner that makes it look beautiful above all else), but what purpose are they supposed to serve? The monotonous accumulation of information about how humanity has thoroughly screwed the planet intensifies environmental grief, the feeling of helplessness and apathy. Films showing what can be changed and issuing calls to action are more necessary than those that penitently repeat over and over again everything that we have done wrong as a civilisation. We already know that.

Lake of Fire (2006)

Though two and a half hours may seem excessive, Lake of Fire never starts to become boring, which is due to the abundance of exotics, freaks, racists, homophobes and bigoted “pro-life” Catholics who preach about how homosexuals roast new-borns on a spit. For the same reason, despite the effort to constantly shift perspectives rather than offer a serious treatise on a serious subject, the film is reminiscent of a hysterical freakshow without a concept (which is not very surprising in the case of a film from a director with no previous filmmaking experience), a mashup of best-of moments from the television news, where those who cry the loudest generally end up. What matters is not whether the given person’s opinion makes any sense and offers something new opinion, but whether it is sufficiently extreme and offensive. This also corresponds to the lack of interest in the deeper motivation for the given belief system. We predominately hear shouts ripped from their context (though it is clear that many of the film’s subjects would give the impression of being psychopaths regardless of how much additional information we may have about them). Only a few older white men, who may have several academic degrees, calmly present their arguments, but – pardon my language - they don’t know shit about what a woman goes through before having an abortion (it is remarkable, though not very surprising, that the “pro-life” group is composed predominantly of men who are most likely terrified by the fact that a woman could freely decide on existence or non-existence). Tony Kaye attempts to make his film as attractive, or rather as shocking as possible, so you sometimes wonder whether you are watching an advertisement, video clip or exploitation horror film, which is also supported by the choice of the “artistic” black-and-white format, which distances us from reality rather than bringing us closer to it (e.g. the sight of blood is more disturbing when you see it in colour). The most substantial element is his epic, though certainly not “definitive” treatise on the ideological war around abortion in the calmest and seemingly most mundane moments when, following the model of the Verist school, he quietly captures rather ordinary dialogue through which the film finally brings forth something significant (the physician’s conversation with Stacey). Regardless of the many reservations we may have with respect to his approach, which gives preference to strong emotions over reasonable discussion, this sixteen-year-old film is a respectable work and is again particularly relevant in today’s climate, when whinging white men with a narrow range of knowledge and low intellect claim to be the masters of the world. 70%

Bacurau (2019)

“This is only the beginning.” Transplant Schorm’s The Seventh Day, the Eighth Night into the Brazilian sertão, add tropicalism, Italian westerns and American B-movies (especially action and sci-fi), political satire, electronic music, extreme violence, a carnivalesque blend of disparate elements, the (Bakhtinian) logic of excess, grotesqueness and corporeality, the lack of differentiation between the categories of “high” and “low” art, a mix of social criticism and a utopian vision of a community that preserves the traditions of Brazilian culture and Udo Kier... and you will have only a vague idea of the truly strange nature of this film, which – like the village that serves as its title – rebels against the seamless fusion of different cultures. One of the most striking and refreshing yet, at the same time, most difficult-to-describe film experiences of the year. 80%

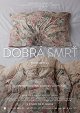

Dobrá smrť (2018)

The Good Death is a documentary portrait of an English woman who intends to undergo euthanasia. Seventy-two-year-old Janet does not want to wait until her unfortunate health condition, caused by hereditary muscular dystrophy, deteriorates to such an extent that she becomes completely legally incompetent. She would lose the ability to make her own decisions supported by clear, rational arguments. She is not afraid of death. She has accepted it just as she previously accepted her illness and the fact that life is not fair and that it is necessary to deal with it in accordance with her current options (unfortunately, the film does not elaborate on the fact that not everyone in her situation has the same options and a "good" death is a kind of privilege, but I understand that such an exploration would be a detour from the direction in which the film’s attention is focused). While Janet determinedly and resignedly approaches the day when the pentobarbital solution will end her suffering, we follow in parallel the story of her son, who suffers from the same disease and anticipates the same fate.___Despite the apparent similarities in the way both social actors are filmed, however, her son’s storyline is more hopeful, as Simon is involved in research that could lead to the discovery of treatments for the currently incurable disease. The impressive visual concept, the use of contrasts and parallels, the heroine’s poetic off-screen commentary and the unforced mise-en-scène to illuminate Janet’s previous life keep the film in the space between procedural drama and open-minded consideration of how death is “natural” (two religious commentaries on euthanasia were typically included in the film – according to one, God should decide on our existence and non-existence; according to the other, God does not want us to suffer and it is therefore acceptable if we decide to end our own lives). Despite the occasional intensification of the melodramatic level through the use of mournful music and the aestheticisation of actions connected with one’s final affairs, the film does not resort to the exploitation of human misery. It is shot with great humility and understanding both for those who have decided to leave and for those who remain. 70%

El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie (2019)

El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie is a solid addition to the best series of all time. In this slow-burning thriller that only gradually reveals necessary information (we always know less than the protagonist), each perfect shot is followed by another and every step of Jesse Pinkman’s ongoing struggle (finally) gets luxurious space. In the spirit of the series, the film essentially involves several longer scenes focused on capturing a certain process, with superbly built tension and often with an unexpected point (connected particularly with the doling out of information and our uncertainty with respect to who is bluffing). The film does not fundamentally expand the Breaking Bad universe, but it very well fulfils its ambition of being additional recognition of Pinkman as the true tragic hero of the series. This is due, among other things, to the narrative structure that switches elegantly between past and present. In addition to the story of the desperate desire to escape (and the impossibility of returning), we see a predominantly melancholic yet, in places, very humorous retelling of how Jesse’s meeting with Heisenberg first filled him with hope and then deprived him of all hope. If you have not seen Breaking Bad, the film of course will not have much meaning for you. If, however, you have seen it, the many references to the series (visual, dialogue, situational) will soon have you captivated. 85%

Synonymes (2019)

Synonyms is an unresolved, fluid film full of ellipses and disturbing moods, which seeks its voice until the end. Like its uprooted protagonist, who reassembles his identity from the numerous fragments that comprise the film’s narrative, it is both stimulating and irritating due to its variability and volatility (manifested not only across the film, but sometimes within a single shot, which sets elements against each other in various image plans). We cannot uncover the essence of the enigmatic protagonist, as he is constantly on the move, always looking for himself and the right words. He can neither abandon his erstwhile identity nor assimilate in a new country. He fails again and again and starts over (System Crasher has a similar structure, but it starts to be monotonous after an hour, whereas that does not happen with Synonyms). With its nervous rhythm (flashbacks from the Israeli army serve not so much for explanation, but for setting the rhythm) and the synonymous varying of one (unresolvable) situation, the film superbly captures the energy (rather than the psychology) of the protagonist. 80%

Wonder Wheel (2017)

There are a few (and really not many more than a few) amusing moments in Wonder Wheel, but seriously, this is not a comedy, but rather an inaccessible relationship drama in the spirit of Eugene O'Neill's plays. Just as the main female protagonist is torn between her boorish husband and an unreliable lover, the entirety of Wonder Wheel is in conflict between a dazzling visual aspect with extremely kitschy compositions and golden light-infused shots and the sad stories of unhappy characters (which are in defiance of the deliberately unnatural retro stylisation, which gives the impression that the characters are moving about in theatrical scenery). I enjoyed the unintentional (?) overlap of two incompatible styles more than the banal relationship mishaps, diffident acting performances, dialogue written without wit or humour and the rigid directing (the proven shot/countershot technique in dialogue scenes, which comprise approximately 98% of the film, is only rarely supplanted by a longer shot with a more sophisticated intra-shot montage). The saddest thing is that this is clearly not a film by a talentless filmmaker. He primarily gives the impression of being terribly lazy, avoiding the effort to pull more out of himself. Again, the work of a tired artist from which the viewer will also walk away feeling tired. 50%

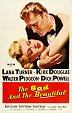

The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)

“You’re business, I’m company.” Following the model of Citizen Kane, The Bad and the Beautiful is a non-linear story about the dark corners of a dream factory. In addition to the hectic pace and extraordinarily cynical insight into a world of unfulfilled ambitions, in which work has precedence over family and money over life, the film is appealing due to the application of the concept of an unreliable narrator. None of the three characters recalling the story has great respect for Shields, who embodies the moral corruption of Hollywood, which is in line with their critical views. However, as is clear from the caustic point, this could be the result of their effort to cast themselves in a better light and not to show how seductive show business actually seems to them. In retrospect, we are forced to reconsider, for example, the cynicism of the first narrator, who seems indifferent to the superficial shine of Hollywood and outwardly perceives it as a game of rich and famous yet inferior people. A comparable degree of self-stylisation is also evident in the manner in which the other two narrators express themselves, as they are equally unsuccessful in their attempt to break through. The concept of Hollywood as a place that produces fictional stories and fake emotions is thus also contained in the formal grasp of the theme. 80%