Recensie (886)

Buiten dienst (1984)

From a simple premise involving four people trapped in an elevator, Carl Schenkel managed to draw out not only an excellent suspense thriller, but also a surprisingly layered depiction of masculine crises and frustrations. The elevator shaft becomes a minimalist metaphor for the capitalist system of lifelong careers and the three men of different ages mirror different phases of “productive” life, which inevitably collide through assertions of masculinity. Much more than the stuck elevator, the trapped characters are threatened by their blindness, touchiness, vanity and weakened self-assurance. The film’s sole female character finds herself trapped between the egos of these men, but despite the initial impression that she gives, she definitely does not prove to be a one-dimensional victim. Schenkel maintains the suspense and shifts the dynamic between the characters by gradually revealing their personal motivations and backgrounds. Beyond that, Jacques Steyn’s impressive camerawork also deserves praise. In addition to some remarkable exhibition shots, it manages to flawlessly escalate the atmosphere and develop the intensifying drama through effective framing in the confined space.

The Matrix Resurrections (2021)

The fourth Matrix comes with the ambition to show what has happened in all of the worlds since Neo’s seemingly last breath, i.e. not just the cinematic worlds inside The Matrix and the Matrix, but also the filmmaking and audience worlds outside of it. However, what the new film presents inadvertently proves to be much more thought-provoking than what it literally presents in particular instances of dialogue and scenes. Much has been made of how Lana, with her presumed absolute creative control, took the liberty of making a cheeky joke at the expense of Hollywood and its contemporary trends and pursuit of viewer comfort. Despite all of that, however, The Matrix Resurrections is not the rumoured anomaly, but in the end it largely remains merely another manifestation of the system. The greatest expression of creative freedom within the Matrix franchise remains the third instalment, which, in spite of everything, follows its own lighted path of techno-new age ethos and aesthetics in the style of The Watchtower. Conversely, the new Matrix notably ignores all of these levels. Instead of spirituality and philosophy, it dawdles over purely secular issues, and virtual ones at that. Whereas for some viewers this will be a confirmation of the fall of today’s world from the heights of thought into a self-indulgent presentation of its own would-be sophistication, from a step farther way, the effort to awaken that world may appear. Religionist interpreters of the original trilogy, according to whom its individual episodes correspond to the stages of awakening, contradiction and enlightenment, may see this as a step backward, whereby the franchise returns from nirvana to earthly matters, back to the marketing-heralded beginning. That may just be exactly what the world needs today. Not to accept an old messiah from a long-ago age, but to understand that the current stage of society is still not perfect, that true progress – technical and intellectual – never ends or, in the better case, we are still only at the beginning, only with a starting position that has shifted. It’s a similar case with everything that viewers expect from the new Matrix, at least in the sense of our expectations and, conversely, what Lana Wachowski is aiming for. Those who associate the three preceding instalments with innovation or progress in the area of action scenes will be disappointed or utterly pissed off by the confrontational ridicule that the fourth film offers. However, those who expect the Wachowskis’ work to go in new directions (through assimilation of the progress made by others before them) will not be disappointed. The Wachowskis have long been interested not in action scenes, but in the possibilities of narrative and the depiction of movement, and ideally the combination of both. Therefore, it may come as a surprise that The Matrix Resurrections makes very little use of Reeves’s impressive physical skills from years of working on the John Wick franchise. Some of the action scenes even feel completely haphazard. From the overall perspective, however, it can rather be said that they correspond to Neo’s gradual recollection of his abilities and it’s no longer about making the action an attraction, but they have already done that. The film is even more fascinating in the key dialogue scene and the variations thereof spread out over time and space, where the revolution in means of expression takes place. In many respects, the fourth Matrix is an even more inconsistent and, in its individual aspects, problematic work than the Wachowskis’ projects that immediately preceded it. But, again, it’s true that it offers something new, unseen before, fascinating and thought-provoking.

World of Tomorrow (2015)

Young Emily and her clone from the future desperately seeking the meaning of their own existence and longing for fulfilment in a world heading toward disaster. Or the animator Don Hertzfeldt taking his first steps in the field of computer animation, accompanied by his four-year-old niece, Winona. Childlike guilelessness and playfulness as a beautifully terrifying abyss into which a mind burdened by philosophical-existential anxieties gazes.

World of Tomorrow Episode Three: The Absent Destinations of David Prime (2020)

Hertzfeldt’s World of Tomorrow trilogy is a flawless demonstration of the power of animation as an expressive medium, where the only limitation is the creators’ imagination. What Christopher Nolan, for example, arduously strives for on the foundation of a big-budget blockbuster and a crew of thousands, Hertzfeldt is able to do and even surpass with a short film involving a tiny group of collaborators. The cunning existential absurdity about time travel and cloning and the effect thereof on free will, destiny and identity is disarming in its complexity, profundity and caustic humour, rollicking playfulness and stinging emotionality. Furthermore, the number of episodes within the (for now) trilogy does not indicate the number of offshoots from the successful source, as would be the case in the mainstream. In Hertzfeldt’s case, on the contrary, it is an expression of power – not only in relation to the original concept and ideas of the first World of Tomorrow, but also in terms of the creative process and animation technology.

Petrov's Flu (2021)

In his feverish hallucination of contemporary Russia and its ties to the past, Serebrennikov reels between Altmanesque mosaic, festival exploitation and an ostentatious display of his own abilities as a director. It is definitely necessary to tip one’s hat to the expansively elaborate yet natural-seeming mise-en-scene in combination with the long, complicated tracking shots. But the moment you understand that the fever is a justification for the fact that absolutely anything is possible, it takes the wind out of the sails of the premise consisting in the contrast between the helpless and aimless lives of ordinary people against their materialising fantasies, where they vent their frustrations in escapades of strength. What remains is primarily a spectacularly delirious formalistic exhibition and treatise on Russia, which characteristically bubbles over despite any attempt to somehow generally deal with it.

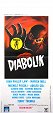

Diabolik (1968)

When describing Danger: Diabolik, allusions to Fantomas, Barbarella and the Batman series of the same period pop up in abundance, but if there is anything to which this magnificently naïve and visually flawless film comes closest, it is the comics of Kája Saudek. Through their framing, mise-en-scene and specific decorative artefacts, some of the shots seem to directly evoke individual panels of the pop-art master, and that’s not even to mention the casting of the central duo, whose ethereal, statuesque nature seems to come to life directly from his drawings. Unlike the unbridled playfulness and humorous exaggeration of the films mentioned above, Danger: Diabolik works with the self-confessed naïveté, artificiality and absurd (anti-)logic of trashy comic books, which it indulgently depicts and takes delight in the fact that it wants to be more comic-bookish or rather more unrealistic than its source work.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973)

Yates hooks the audience with a heist concept, but instead of a standard genre flick, he lays out before them a coolly reserved yet fascinating crime movie about the unpredictable nature of life at the edge of the law. Furthermore, without prior knowledge of the plot, the narrative is a labyrinth in which various characters move around, as their relationships with each other and their roles in the entire criminal structure are only gradually revealed. The screenplay uses this not for dramatic twists, but rather for the purpose of building supense and concurrently conveying the cynicism of the criminal underworld and officers of the law, where no one knows who is going to go for his throat or sell him out for the illusion of redemption. To a significant extent, the characters’ relationships thus mirror the heists, which actually serve as metaphorical parallels. We first glimpse the ideal scenario, but even though we see that it is feasible and fulfillable, it doesn’t diminish the suspense of the next heist, of whether something will go sideways and what the consequences of that will be.

Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar (2021)

Barb and Star is a half-dried-up SpongeBob for people in their forties who make fun of people in their sixties, where imagination is replaced by gossip about tits and where the greatest transgression consists in the realisation that you are watching a movie about your mom.

The French Dispatch (2021)

The more recent Anderson’s films, the less animate the dolls he plays with, but they inhabit grander and more decorous rooms. The paradox of his tribute to the floridly descriptive and snobbishly authorial style of journalism consists in the fact that his film highlights its artificiality and illusoriness.

The Mitchells vs. the Machines (2021)

In terms of the screenplay, The Mitchells vs. The Machines is not in any way innovative, as it merely remains solidly functional within its predictable narrative. However, the film’s main strengths consist in its visual aspect and how it solves or rather overcomes the essential problems of computer animation. The animation moves between the two poles of (hyper-)realism and abstraction. The best animators are able to combine realism and stylisation into a functional whole in their work. For example, Chuck Jones’s masterful grotesques violate the laws of physics, but they concurrently make essential use of physicality and physical logic in everything from the fall of an anvil to the smallest gestures of the characters. Jones created characters that were simultaneously complete and cohesive, but also tremendously flexible and chaotic because the medium of classic animation allowed him to do that. With the rise and dominance of computer animation, which works with virtual models or, better said, puppets with a solid skeleton, the work process has become faster and more efficient, but it has also lost its expressiveness. At least that applies to mainstream animated feature films, where the main trends were set by the pioneering Pixar, whose aim was to achieve maximum photorealism. In parallel with its milestones in this respect, Sony Animation conversely (alongside profitable franchises) sought ways to come up with something new in the context of the technology used by everyone, and mainly to bring stylisation and non-realism back to computer animation. The Mitchells vs. The Machines follows in the footsteps of not only the revolutionary revelation Spider-Man: Parallel Worlds, but also of its more obscure but developmentally essential predecessors – the cartoon-stylised 3D animated movies Hotel Transylvania and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, as well as the studio's first experiment, the animated found-footage flick Surf’s Up. Though Parallel Worlds was extraordinarily delightful in comparison with the animated feature films of the time, it remained bound by the aesthetics and expressive devices of comic books. In The Mitchells vs. The Machines, such boundaries fall away and an even bolder style comes forth, which this time openly refers to online creative work, not only on YouTube, but mainly on newer platforms like Instagram and TikTok with built-in creative and expressive tools. It is obvious from the project that the age of its creative team ranges from 40-somethings to the recent art-school graduates who populate the animation, storyboard and visual design departments. If we use references to describe the result, we see the expressive colourfulness of Speed Racer, the lighting design of Tron: Legacy and the madcap physical expressiveness and meta-genre self-reflective playfulness of The Amazing World of Gumball, all covered with a layer of stickers, emojis and memes from the aforementioned social networks. Unlike other films that attempt to somehow incorporate into themselves the internet’s characteristic means of expression, here the filmmakers rarely use existing resources and conversely come up with their own emojis in the form of distinctive doodles. Beyond that, they set the goal that 3D animation should look like painted reference images with their characteristic colouring and painted shading. The feature film Klaus had already gone a long way in this direction, but here a completely different and much more sophisticated technology of painted shading and dynamic edge lines is employed. All of this serves to reinforce the impression of “cartoonishness”, which also unties the animators’ hands in terms of the wildness that they can allow themselves in the creative preparation of individual action, melodramatic and comic moments. Some viewers who are used to the nonsensical pseudo-realism of animated blockbusters will be irritated by The Mitchells vs. The Machines due to its schizophrenia in the constant frenetic switching between seriousness and cartoonish boisterousness, dynamic physicality and absolute mockery of physics, as well as the blending of dramatic pathos with unbridled imagination. Others, however, will love the film thanks to the fact that it breaks down the monolithic style of animated blockbusters and brings back wackiness and creativity that is finally unhindred by technology.