Recensie (886)

Popeye (1980)

Directed by Robert Altman and starring Robin Williams, the burlesque musical Popeye (1980) was one of two rare co-productions between Disney and Paramount (the other being the phenomenal The Kite Runner). It was made in Disney’s so-called “dark age”, which is demonised in the official historiography because the then-boss Ron W. Miller steered the studio away from its values, which are still extolled to this day. But like other projects made under Miller’s management, Popeye is a distinctive and ambitious work, and an underrated, though bizarre, gem. According to the narrow-minded interpreters of Altman’s filmography, however, this spectacularly phantasmagorical project is often considered to be a misstep or a film made only for the money. It is in fact a unique attempt to translate a cartoon world, with its characteristic rhythmic dynamics, visual chaos, nonsensical logic and physical elasticity of the characters, into a live-action format. Furthermore, on closer inspection the narrative, which presents to viewers not only the titular protagonist, but also an entire maritime town with all kinds of odd characters, comes across as a cheerfully absurdist paraphrase of Altman’s iconic mosaics of tragicomic life stories. As in his early gem Brewster McCloud, Altman shows off both his neglected comedic side and his subversion of classic Hollywood formats, particularly burlesque, musicals and big-budget costume flicks. It is no coincidence that Paul Thomas Anderson, a great admirer of Altman, incorporated a wonderful homage to Popeye into his own similarly polarizing gem, Punch-Drunk Love (2002).

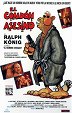

Kondom des Grauens (1996)

Killer Condom is a likable camp project, not only in terms of viewer optics, but also in its creative roots. The film was created based on motifs from the comic book of the same name by leading German queer author Ralf König, who over the course of years rose from the underground to a place in the sun thanks, among other things, to the strong popularity of the film adaptation of another one of his works, The Most Desired Man (1994). Whereas in that case the adaptation smoothed out the edges of König’s source material, Killer Condom adds even more queer and camp levels to those found in the original short comic book. The result comes across a bit as if John Waters had decided to make a mix of hardboiled noir and a 1950s B-movie with monsters and mad scientists. Faithfulness to the source material (after all, Killer Condom begins with the credit “A Ralf König Film”) is also evident in the New York setting, as the filmmakers have an absolute field day with depicting the decadent and debauched world, which they do not demonise, but openly adore while revelling in caricaturing its iconic attributes and images from mainstream films. The film adaptation of Killer Condom is thus even more of a queer camp paraphrase of the trash genre than the original comic book and is similarly impressive with its proudly queer characters and paraphrases of genre formulas. ___ PS: Troma said it would only buy a weird German film for American distribution. Kaufman and co. had nothing at all to do with the making of Killer Condom.

Das Deutsche Kettensägen Massaker (1990)

In the second part of his loosely connected trilogy about Germany, Schlingensief presents a metaphor for the reunification of Germany and the relationship between West and East Germans, again in his characteristic hysterical meta-style. He tellingly and admittedly took inspiration from the classic horror flick The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. However, he didn’t use that film as the basis for some sort of remake or reflection on the genre, but in a typically punk spirit as a completely absurd standpoint from which he views his subject. Schlingensief’s provocation consists in his upending of the discourse of that time that depicted East Germans as those who came to feed off of years of western development. Contrary to that, The German Chainsaw Massacre shows West Germans as affected degenerates who, through a sense of privilege, appropriate everything and literally parasitize the East Germans who naïvely and guilelessly come to the West.

Das Millionenspiel (1970) (Tv-film)

The Millions Game is further proof that the overused “quality TV” formula, though an outstanding marketing construct that succeeded in foisting itself on both viewers and critics, is a malicious tool for diverting attention away from the history of television production. The term implicitly expresses that television has become something ambitious or even pioneering only in the new millennium and that, in terms of quality, it had previously lagged behind cinema, which it caught up with in the 2000s and subsequently surpassed (as the PR departments of broadcasters and streaming services try to tell us). In cooperation with screenwriter Wolfgang Meng, Tom Toelle, one of a number of ambitious filmmakers who purposefully worked with the formats and possibilities of the small-screen medium, transformed Robert Sheckley’s book into an iconoclastic provocation that still raises a lot of questions that television would prefer not to ask, as they undermine its very nature as fiction passed off as reality. The Millions Game was made several years before television began to be reflected in mainstream cinema in films like Network (1976) and The China Syndrome (1979), but it also paralleled the iconoclastic work of Peter Watkins, though before his peak experiment Punishment Park (1971), not to mention The Running Man (1987) and the book on which it was based, to which The Millions Game is most frequently compared. The genius of Toelle’s experiment is shown not only in the way it fits into the mould of ordinary television by jumping from the format of news reporting to in-studio variety show and hyper-aestheticised commercials, but also in its use of the genre conventions of thrillers and subversion of those conventions through alternating perspectives and glimpses behind the scenes. Among other things, the subversive nature of this television project consists in the fact that it surreptitiously presents fragmentation, randomness and the artificial creation of tension as essential features of television entertainment. Furthermore, whereas Stephen King and the adaptation of his book toothlessly showed a dystopian future in which television entertainment is one of the by-products or parallel instruments of control, Toelle and his collaborators saw the reality-show format itself as a future dystopia. And now we know they were right.

Feuer, Eis & Dynamit (1990)

Fire, Ice & Dynamite is the absolute pinnacle of the cinema of attractions. The absurd and blatantly shaky plot justifies the bombastic power of Jeux sans frontières and Red Bull Cup. Willy Bogner created and shot the skiing sequences for several Bond movies, but he was always disappointed that the sports action in those films never accounted for more than ten percent of the runtime. His whole filmography was aimed at reversing this ratio, and Fire, Ice & Dynamite is in a certain way the culmination of that effort. That’s not because there is no plot (that didn’t come until much later films), but because it is so blatantly absurd. However, it remains functional, as it justifies the endless deluge of attractions of every kind, including insipid verbal and slapstick humour, hit songs on the soundtrack, spectacularly insane product placement and cameo appearances by all manner of international celebrities. But the lead role is played by individual phantasmagorical disciplines in captivating natural settings and the breakneck conquering of those settings. It’s not about who wins, but about the various obstacles that can be placed in the athletes’ way to arouse the greatest possible astonishment by depicting them as effectively as possible. Sure, that is the antithesis and total vulgarisation of the principles of the action blockbuster, but at least in the ratio of spectacle to total runtime, no one in the world, neither in Hollywood nor in Hong Kong, could match the German tycoon Bogner and his phantasmagorical extravaganza across the elements (at least until the arrival of Mad Max: Fury Road).

Kdyby radši hořelo (2022)

An unexpectedly effective combination of empathetic naturalistic humanity in the spirit of Jaroslav Papoušek and the style of Takeshi Kitano with his deadpan humour infused with melancholy and modelled on comic strips in static shots oriented directly toward the camera. And dry humour that is suitably chilling. Plus extra points for the great use of music under the closing credits (stay until the end).

Charley Varrick (1973)

Charley Varrick is a delightful masterclass in storytelling, dealing with the titular bank robber whose latest job didn’t go according to plan and he thus has to rely on his experience to get away and cover his tracks. Like the seemingly apathetic protagonist who is actually a farsighted planner, the script also proceeds in relation to the viewers. With utter joy, we watch the individual casually stylish characters, around whom the film builds our expectations of how they will behave in a certain inevitable situation that is about to occur. We get the same pleasure from noticing how the film, as if incidentally, lays the groundwork for all of the upcoming twists and turns, or rather the resolution of snowballing peripetias. As a result, Charley Varrick is captivating as a good genre flick with light humour that kicks into high gear immediately, but runs so smoothly because it is well thought out to the smallest detail and precisely directed.

Ubal a zmiz (2021)

We have seen it before from Guy Ritchie, and the whole thing is obviously cheaper, or rather it lacks the stylistic ambition and force of Ritchie's debut, which intentionally used an imaginative and, for its time, progressive formalistic rendering to draw attention away from its shabby origins. At the same time, however, Punch and Run relies on a fine screenplay with superbly drawn characters, which are excellently fleshed out by the casting. With his likable debut, Hobzík sets himself apart from Ritchie and those who followed him primarily with the way he works with the genius loci of Prague's Žižkov neighbourhood, which invites similarly exaggerated and cartoonishly skewed genre puns.

Top Gun: Maverick (2022)

In Mission: Impossible – Fallout there were several sequences when the film crossed the line of fiction and built an exalted monument not only to its protagonist, but also to the actor who portrayed him. Top Gun: Maverick works simultaneously at the levels of fiction, reflective adoration and meta-commentary. Thus, when the line “The end is inevitable, Maverick. Your kind is headed for extinction” is uttered and Maverick responds, “Maybe so, sir. But not today”, it’s not just the title character or Tom Cruise, as the last thoroughbred Hollywood star, speaking for himself, but also for the 1980s blockbuster model. All of the warning lights are blinking red, alerting us that this old/old-world colossus shouldn’t be able to stand up to the bigger, faster, more finely tuned competition made with the latest hardware and software. We constantly have the feeling that this isn’t how it’s done anymore, that the time for that has passed, that everybody wants something more sophisticated, more advanced and more contemporary. But here it is simply confirmed that it is not the machine that matters, but the pilot. Of course, there are cheesy camp and crypto-queer levels to the film, but judging by the audience’s reaction, these are not flaws, but part of a delightful viewing experience, as the film doesn’t just wink at the viewers, but looks them right in the eye with its hard-to-resist gaze. Also, following Žižek’s analysis of Rammstein’s music and concerts in relation to Nazism, we can even say that the second Top Gun gives us a passive experience with Scientology (though, unlike in the case of Rammstein, this is not all based on caricature and it certainly does not subvert the reflected ideology). Tom Cruise can be condemned and hated for a number of things, but unlike other megalomaniacs of our time, he cannot be denied the recognition that he is without equal in his field, i.e. in cinematic spectacles. Not because of the massive paydays that he receives or how he fleeces his subordinates, but rather because he can tear down everyone for the perfectionist vision that he has worked so hard to create. Top Gun: Maverick proudly shows off its banal and obsolete engine, which should be in the salvage yard, but the living awe generator working the stick squeezes more power out of the old beater than anyone before him. ___ Footnote: In a handful of melancholically dreamy moments and plot motifs, Cruise’s ode to flying evokes Miyazaki’s understandably more poetic and multi-layered monument to fighter aces, Porco Rosso.

Medusa Deluxe (2022)

Thomas Hardiman’s debut has such a fascinating concept that you want to forgive him for the fact that it can’t work because of its thorough fulfilment. A one-shot detective flick without a detective in the backstage area of a hairdressing competition, Medusa Deluxe is actually the cinematic equivalent of the hairstyles found in the film, which are utterly self-indulgent, superficial, intricately constructed and admirable mainly due to the amount of work and passion put into them. Paradoxically and peculiarly, the film confirms the rule that the last few minutes of a movie are decisive for the viewer’s overall impression of it. Specifically, you will leave feeling good, though mainly thanks to the great dance number that comprises the end credits and is, unfortunately, also the best part of the entire film. Nevertheless, as a first film, Medusa Deluxe works in that it draws attention to its creator. It will definitely be interesting to see what Thomas Hardiman makes next, especially if he manages to step out of the shadow of his acknowledged influences. As it stands now, however, he merely offers a weak rehash of Gaspar Noé’s aesthetics and Robert Altman’s narrative voice. [screening at the Marché du Film in Cannes]