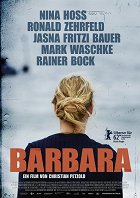

Regie:

Christian PetzoldScenario:

Christian PetzoldCamera:

Hans FrommMuziek:

Stefan WillActeurs:

Nina Hoss, Ronald Zehrfeld, Rainer Bock, Deniz Petzold, Jasna Fritzi Bauer, Peer-Uwe Teska, Mark Waschke, Kirsten Block, Susanne Bormann (meer)Samenvattingen(1)

Oost-Duitsland, de zomer van 1980. De jonge arts Barbara wil het land verlaten en heeft een uitreisvisum aangevraagd. Dit verzoek wordt door de overheid echter niet gehonoreerd en ze wordt zelfs naar de provincie verbannen. Babara moet Berlijn verlaten om in een klein plattelandsziekenhuis te gaan werken. Zij hoopt dat haar geliefde Jörg, die uit West-Duitsland afkomstig is, hun ontsnapping voorbereidt. Ze bouwt geen nieuw leven op, daar ze wacht op een beter leven. Alleen voor haar patiënten in de kinderchirurgie heeft ze nog affectie. Haar baas André waardeert haar werk, maar besteedt wel erg veel aandacht aan haar. Behoort hij tot de Stasi? Of is hij verliefd op haar? Barbara weet het niet en de geplande vlucht lijkt steeds dichterbij te komen... (A-Film Benelux)

(meer)Recensie (2)

Barbara is a solid drama, though unfortunately with a somewhat soap-opera-like ending that shows some lazy

screenwriting.

()

Barbara is a gem, and not only in comparison with strained, black-and-white Czech cinematic throwbacks to the period of normalisation. Petzold doesn’t work with flattening oppositions, as he takes multiple perspectives into account and confronts the titular protagonist with complex moral dilemmas. As with the other characters, Barbara is for us a woman of mystery who is hiding something. We don’t know what she is guilty of or what her intentions are. Based on the mistrustful glances of others, as well as on the way the camera captures her, it is apparent that Barbara is under constant surveillance. With her privacy gone, she has no reason to feel joy. She doesn't believe in happiness; fear is her predominant emotional state. Her helpfulness towards others is selfish. If she needs nothing, she does not allow others to physically approach her and she communicates with them in curt sentences. She prefers to express herself only by playing inoffensive music on the piano. Patients are an exception – a promise that it is possible to do something meaningful even in the depersonalised era of Communist torpor. Thanks to the ambiguous characters, attention to detail (sticking band-aids on ankles, leafing through a Western catalogue) and the subtle production design (the props don’t draw attention to themselves, but are just simply in the shot), the world of East Germany depicted in Barbara seems very authentic and not like an excursion to a museum of Communism. (A nice example of the unforced rendering of the reality of the time is the clash of two worlds, represented by a Trabant and a Mercedes on a forest road.) Whereas Czech filmmakers scream about how all Communists were swine and how hard life was for decent people, Petzold neither slips into such generalisations nor engages in a transparent attack on the system. He touches on the major history through a single small, intimate story, which does not prevent him from simultaneously capturing the atmosphere of the time and posing some timeless questions about a person’s responsibility for others. Barbara is an extraordinarily powerful drama even without powerful language. It simply works. 80%

()